By: Cindy Amos

The Science of Reading is not new and the argument around it’s effectiveness is one that has been going on for decades. Yet many teachers do not understand what the Science of Reading or commonly called SOR would look like in a classroom lesson. Many states, including Indiana have passed legislation that mandates SOR be use to teach reading concepts (Yaden, 2023, p.31). Even so teachers are scrambling to update lessons to be more in compliance with new state laws. Teaching a child to read is a very challenging task as it is not natural for a human to read (Snow, 2021, p.222). This article will explain what the science of reading is, what it should look like in an elementary classroom and how to teach using the Science of Reading to students including those who are exceptional learners?

So what is the Science of Reading?

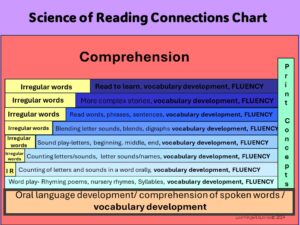

First what is the Science of Reading? The Science of Reading, as described by the National Reading Panel, consists of teaching reading using highly researched components that include phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension (Howe, & Roop, 2021, p1). These components when working together have proven to increase reading scores for all children including those with exceptional needs. The implications of this understanding could be that elementary teachers are given the essential information to effectively teach students, even those with exceptional needs not limited to dyslexia how to read with a mastery level of 95% of students being proficient readers (Petscher et al, 2020, p271). Ellis et al state in the National Council on Teacher Quality review of reading there are five components needed to teach a child to read: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension (Ellis, 2023). Research has shown that “there is a systematic way to present information to students. Biggest chunks to smallest increments to more complex elements” (Ramzy & Bence, 2022, p.12).

Teaching reading is not an easy task. It requires skill and best practices that are based on research and evidence. Most educators and researchers agree the phonemic awareness is a must for beginning readers, but recent research has linked language development from birth as a key component to learning to read. Language is the way infants and toddlers seek to get their needs met. From this give and take with their adult caregivers comes a child’s development of vocabulary, oral language, and the ability to understand the spoken word (Snow, 2021, p228). This period from birth to preschool begins the building of schema or background knowledge a child has in their memory to use later. Background knowledge is critical to comprehension skills when listening to or reading a text (Hoffman et al, 2021, p89). If a child has never seen a tractor or a race car the child will not understand why either would have different circumstances for safety needs of the driver. Lui found that schema directly impacts all subsequent learning.

Vocabulary also aides comprehension (Yopp &Yopp, 2007, p157). Brandes and McMaster found that vocabulary and comprehension offer mutual aid to each other. This may lead to a child reading more frequently and in turn learning more vocabulary. Snow found that on average a first grader can comprehend nearly 10,000 words and use 2,600 words in their speaking. It was also found that children learn to comprehend and manipulate morphologically and syntactically. In other words, they can break words into word parts like– li/ bra/ry to be able to mark syllables, and to read the word. If a child has a smaller vocabulary, they may struggle to have a word to recall automatically when reading a text. This will harm a child’s comprehension. The previously discussed components work together to aide in a child’s fluency, or the ability to read automatically, accurately and using the correct expression. Research has found that 90% of the difficulties students have with comprehension are due to poor oral reading fluency. A student’s word count per minute read is a research-based way of indicating a strong reading fluency. There is evidence that normalizes a child’s WCPM rate increasing between 3rd and 5th grade (Duffy et al, 2024, p538-540).

Both sides of the reading wars agree that a child must have a strong phonemic awareness for a child to be a successful reader (Stahl & Kuhn,1992, p619). Phonemic awareness is not phonics. Phonemic awareness refers to understanding sounds and phonics is about associating letter symbols to those sounds. Phonemic awareness is a bigger predictor of future reading achievement than vocabulary, nonverbal intelligence and listening comprehension, and IQ scores (Yopp, 1995, p20-21). Phonemic awareness is one part of phonological awareness. Phonological awareness is a student’s ability to manipulate sounds is speech as in onset, rimes, phonemes, and syllables. Phonemic awareness is the final, most challenging, and deepest level of comprehending language. Students are asked to think about words from the sounds that make them as in dog (d/o/g) or in wish (w/i/sh). Phonics would ask a child to write these sounds as symbols for the sounds as d-o-g using three letter symbols or wish using four letter symbols for three sounds (Yopp & Yopp, 2009, p12-14). It has also been implied that print concepts need to be added to the core components due to the importance of written text had to mastery of reading. They found the six core components are so intertwined that if one is lacking it then affects the other components negatively (Ramsey & Bence, 2022, p14 -17).Galbally & Schaff found that learning to read can be an extremely arduous task, only second to the intricacies of teaching a child how to read.

What about Exceptional Learners ?

The research is clear that the push for the Science of Reading is coming from parent and educator advocating for children who are dyslexic or other who are experiencing reading difficulties. Dyslexia affects 20% of the world and this causes great struggles for them to learn to read proficiently (Klages et al, 2020, p47). Yaden found that there is no prescribed method to diagnose dyslexia and other argue it is not a real malady. Still others counterpoint that dyslexia is a learning disability that is specific and neurobiological at its core. It can present as trouble reading words accurately and fluently, trouble decoding and spelling words, and is a direct result of lacking phonological skills. This then impacts other components of reading such as comprehension and lack of reading experience due to lack of vocabulary and schema (Klages et al, 2020, p47-48).

The Science of Reading requires that all children are given explicit instruction in the core five components of reading including phonics and phonemic awareness. This is an area that most researchers agree, including the National Reading Panel, is predictive of a child’s status as a good reader. The areas these children have the most difficulty is letter to sound matching, being able to blend sounds heard in a printed word, and to rapidly name letters. This is called the alphabetic principle or the ability to correlate a sound into a letter symbol. Another important component is phonological awareness. This is any activity that requires a child to manipulate sounds and can include rhyming, blending sounds and matching beginning, middle and ending sounds to a word. Without this skill, children are not able to read independently and often have reading difficulties in the future (McNamara &et al, 2005, p85). It makes sense then to teach all children using explicit instruction using the five core components. As most children are not introduced to such methods until kindergarten, they are also being tested for difficulties in these areas until entering formal schooling. Educators should state what is being taught and demonstrate how to perform a task. Engaging tasks should give students time to learn in a conducive environment where they can demonstrate and practice new principles of each lesson (Klagen & et al, 2020, p47-48).

There has been research that has proven the Whole Language approach and the Simple View of Reading to be effective in teaching a child how to read (Snow, 2021, p229). Whole language became the trend method in the 1980’s and has only recently fallen out of the mainstream with a renewed push towards the use of phonics to teach reading. This has led to new laws requiring the use of the Science of Reading to be taught in elementary schools across the country. Advocates for the Science of Reading point to the Big 5 components to teach reading: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. They have found that these need to be taught explicitly and systematically for all children to become successful readers. While proponents of Whole Language believe printed items need to be present for a child learn to read by being in the vicinity of the written words.

Jean Chall advocated strongly for the use of teaching phonics and phonemic awareness to teach a child to read proficiently. She and others have found that children who are taught to understand phonemes and their corresponding letters become more fluent readers (Semingson & Kerns, 2021, pS157- S161). All the research has been connected to be called the Science of Reading. Some argue that this only means teaching phonics and phonemic awareness and have pushed to have new laws and mandatory remedial trainings of teachers to learn how to teach the using phonics. Many feel this is a narrow view of what the actual research and evidence do show to be effective when teaching a student to read (Hoffman et al, 2021, p87). They argue that there are over 14,000 peer reviewed articles on the topic of reading and educators need to use this research to prepare research-based lessons (Petscher et al, 2020, p267). Still others have stated that most teachers do not have access to these articles, and many do not have the time to read current research (Kretlow & Blatz, 2011, p10). The National Education Policy Center state the science is more complex and is not settled. They believe the push is clearly political and needs to be tampered with allowing educators to provide individualized instruction based on student’s need and each student’s understanding of material being taught based on professional experience and knowledge.

What Should SOR Look Like in a Classroom?

There is a plethora of research on what should be taught in an elementary reading lesson. Research has not shown the timing of introducing each of the components for optimal gains in reading ability. Reading teachers need to know when to introduce phonological awareness components to develop phonemic awareness which research has proven to be a critical piece of learning to read (Yopp, 1995, p20-21). The research shows how each of the five components are intertwined and influence the knowledge base of each other, because of this teachers should use all five components: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension, in daily lessons. Starting with the biggest pieces of language including rhymes, words, names and moving toward the smallest more difficult pieces including phonemes or individual sounds in words teachers will see optimal results in student achievement (Ramzy & Bence, 2022, p.12). Research states that 95% of all students should be able to read proficiently (Snow, 2021, p.222).

Teachers need to begin by using word games with students, rhymes songs and poems help children begin to identify similarities and differences in words. The graphic shows the interconnectedness of all components to reading. Students are then ready to learn about basic syllable counting while continuing to learn new words to speak and their meaning. Don’t forget about the other components to reading, but phonemic awareness is the component that most research points to being a critical indicator for later reading fluency. Phonemes are the smallest part to of a word that makes sound. They are the reason why cat is not sat. Learning the rules to sounds can be a daunting task for children and time must be spent on sound work daily in the early years for optimal results.

There are 26 letters of the alphabet that make 44 different phonemes. This is accomplished by different letter combinations to make the same sounds( ea, ee, ei, ew, ey, etc.) and letters that make multiple sounds ( c, g, a, e, I, o, u, y). Once a letter sound is taught to students, the name and written symbol needs to be introduced at the same time, Letters are the written symbols for the English language. Students need to be fluent with the sounds of each of the letters to be able to decode words and with the written letter to encode words later. Decoding is sounding out the sounds for each phoneme. Encoding is using the sounds to spell the word correctly.

Phonemic awareness skills can be challenging to master, but the research shows many strategies to practice these skills with students. Mastering sound manipulation can be a game changer for a beginning reader. An example would be:

Teacher: Say bat

Child replies: bat

T: change /b/ to /s/ what word is it now

Child: sat

I’ve compiled several of these phonemic awareness strategies alongside the research that validates its effectiveness. Click the link below to grab these from my these from my TPT store for free!https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Phonemic-Awareness-Activities-Task-Cards-11729046

While this is not the end of what it means to teach a child to read, it is the beginning steps. Check out my other articles that explain other components of teaching a child to read.

References

Brandes, D., & McMaster, K. (2017). A review of morphological analysis strategies on vocabulary outcomes with ELL’s, Insights into Learning Disabilities, 14(1), 53-72.

Duffy, M., Mazzye, D., Storie, M., & Lamb, R. (2024). Professional development and coaching in the science of reading: Impacts on oral reading fluency in comparison norms, International Journal of instruction, 17(1), 533-558.

Ellis, C., Holston, S., Drake, G., Putman, H., Swisher, A., & Peske, H. (2023). Teacher Prep Review: Strengthening Elementary Reading Instruction. Washington, DC: National Council on Teacher Quality.

Hoffman, J., Cabell, S., Barrueco, S., Hollins, E., & Pearson, P. (2021). Critical issues in the science of reading: Striving for a wide-angle view in research, Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice, 70,87-105.

Howe, K., &Roop, T. (2021). Missing pieces and voices: steps for teachers to engage in he science of reading policy and practice. Michigan Reading Journal 54(1), https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mrj/vol54/iss1/9

Indiana Department of Education, (2023), Indiana Language Arts Academic Standards, https://www.in.gov/doe/students/indiana-academic-standards/englishlanguage-arts/

Klages, C., Scholtens, M., Fowler, K., & Frierson, C. (2020). Linking science-based research with a structured literacy program to teach students with dyslexia to read: Connections-OG in 3-D, Reading Improvement, 57(2), 47-57).

Kretlow, A. & Blatz, S. (2011). The ABC’s of evidence-based practice for teachers, Teaching Exceptional Children, 43(5), 8-19.

Lui, Y. (2015). An empirical study of schema theory and its role in reading comprehension, Journal of Language Teaching &Research,6(6), 1349-1356.

McNamara. J., Scissons, M., & Dahleu, J. (2005). A longitudinal study of early identification markers for children at-risk for reading difficulties: the Mathew effect and the challenge of over-identification, Reading Improvement, 42(2), 80-97).

Petscher, Y., Cabell, S., Catts, H., Compton, D., Foorman, B., Hart, S., Lonigan, C.,

Phillips, B., Schatschneider, C., Steacy, L., Terry, N., Wagner, R. (2020). How the science of reading informs 21st-century education, Reading Research Quarterly, 55(S1), S267- S282.

Ramzy, M., Bence, M. (2022). Literacy instruction through the layers of reading development. Early Childhood Education, 48(1), 1-19.

Semingson, P., &Kerns, W. (2021). Where is the evidence? Looking back to Jeanne Chall and enduring debates about the science of reading, Reading Research Quarterly, 56(s1), s157-s169.

Scheffel, D., Lefly, D., Houser, J., (2012). The predictive utility of DIBELS reading assessments for reading comprehension among third grade English language learners and English speaking children, Reading Improvement, 49(3),75-95.

Snow, C. (2021), SOLAR: the science of language and reading, Child Language Teaching and Theory, 37(3), 222-233.

Stahl, S., & Kuhn, M. (2002). Making it sound like language: Developing fluency, The Reading Teacher, 55(6), 582-584.

Thomas, P., (2022). The science of reading movement: The never-ending debate and the need for a different approach to reading instruction, Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center, http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/science-of-reading

Yaden, D., (2023), Chasing Shadows: Why there cannot be a “simple” science of literacy, Literacy Research, Theory, Method, And Practice, 72, 26-49.

Yopp, H. (1995). A test for assessing phonemic awareness in young children, The Reading Teacher, 49(1), 20-29.

Yopp, H., & Yopp, R., (2009). Phonological awareness is child’s play!, Young Children,64 (1), 12-18.

Yopp, H., & Yopp, R., (2007). Ten important words plus: A strategy for building word knowledge, The Reading Teacher,61(2),157-160.